The Roman Rite: Living Tradition, Not a Museum Piece

Part-2 of a Series on Tradition, Deposit of Faith, and How it all Applies to the Catholic Liturgy.

The Liturgy Wars are still raging, more than 50 years after the close of the Second Vatican Council. You might even say it rages hotter today than it ever has, with the Traditional Latin Mass (TLM, or Tridentine Mass) enjoying a brief heyday following Pope Benedict XVI’s motu proprio, Summorum Pontificum, only later to be effectively reversed by Pope Francis in his own motu proprio, Traditionis Custodes. Is the Novus Ordo a rupture of Sacred Tradition? Did the Roman Rite—the backbone of the Catholic Mass—undergo a change that practically protestantized the Mass?

In Part 1 of this short series I attempted to set the foundation for addressing these questions by first explaining what Sacred Tradition is and what it is not. Today, in Part 2, I want to explain what the Roman Rite is, take you through some of its history, and show how it shapes our liturgical life. Down the road in Part 3 we’ll take a little stroll through the Novus Ordo itself, and learn about the Church’s authority over the Mass.

Battle Lines Drawn (But in the Wrong Places)

When Catholics argue about the liturgy today, they’re usually talking past each other. And no, it’s not because one side wants guitars and felt banners while the other side is clutching their Latin missals for dear life. It’s because they’re not even talking about the same thing.

“The Roman Rite isn’t a museum artifact you look at but can’t touch.”

Here’s what I mean. Some Catholics act like the Roman Rite is this single, perfectly preserved Mass that came down from the apostles unchanged and stayed that way until the 1960s when everything went to hell in a handbasket. Others talk like the Mass is basically Play-Doh—moldable, adjustable, whatever works for the current pastoral vibe.

Both camps are wrong. And both miss what the Roman Rite actually is.

The Roman Rite isn’t a museum artifact you look at but can’t touch. It’s also not a blank canvas where the Church just paints whatever it feels like. It’s a living rite with a real history, real authority behind it, and real limits. And if we want to talk about it honestly, we need to understand what those things mean.

What Is the Roman Rite

Let's start simple. The Roman Rite is a specific liturgical system—a set of prayers, ceremonies, and ritual structures used to celebrate the sacraments. It originates from the Church of Rome, the church that St. Peter headed, the foundation of what we today call the Roman Catholic Church. This is the form of worship the Roman Church has used to celebrate the sacraments (especially the Eucharist) over the centuries. This tradition gradually spread from Rome throughout the Western Church, and today it's what most Catholics experience at Mass

But here’s the part people miss: the Roman Rite isn’t just one Mass. It’s a whole family of liturgical forms that share the same Roman roots.

That’s why you can have different historical versions of the Mass, different liturgical calendars, different ceremonial details—all under the Roman Rite umbrella. Different languages, different practices, different emphases. What ties them together isn’t that they look identical or sound identical. It’s that they share the same essential substance and operate under Roman authority.

Think of it like a family tree. You’ve got cousins who look nothing alike, dress differently, have different personalities—but they’re still family because they share the same ancestors and the same DNA.

Emerged, not Invented

In the earliest centuries of Christianity, there was no such thing as a single, universal liturgical script. What there was were shared theological essentials—the Eucharist, the words of institution, Scripture readings, prayer, sacrifice—that every local church celebrated, but they developed genuinely different liturgical rites from those foundations. The church in Antioch developed its own distinct liturgical form. Milan developed what became the Ambrosian Rite. And Rome? Rome developed what we now call the Roman Rite. These weren't just different flavors of the same recipe—they were genuinely different rites, each with its own prayers, structure, and character.

(Follow me X | Insta | TikTok | YouTube | Facebook | Discord

and my personal newsletter, CatholicFirebrand.com)

Think of it like this: if you visited different Christian communities in the 3rd or 4th century, you’d recognize the Mass everywhere you went. But you’d also notice differences in their respective forms. The church in Constantinople might have elaborate, poetic prayers that went on for paragraphs. Rome? Short, direct, to the point. No flowery language. Get in, worship, get out. Clean and simple.

That Roman personality—simple, sober, restrained—never went away. Even as the centuries rolled on and prayers were added and ceremonies became more developed, the Roman Rite kept that characteristic restraint. Concise prayers. Ordered structure. Theological clarity over poetic flourish.

This matters, because it means the Roman Rite has a personality—but not a single frozen form.

Latin Was a Tool, Not the Point

Let’s talk about Latin in the Roman Rite. This is a[n inexcusably] touchy subject that many Catholics get wrong. So I want to start off with some very blunt clarity before I go into the history and explanation: Latin did not define the Roman Rite. It served it. Latin is not part of the Deposit of Faith, it is not Sacred Tradition, and though the Roman Rite developed within Latin, the Latin language is not essential by its nature to the Roman Rite.

Why did Christians in Rome worship in Latin? Because that’s what people spoke. Latin was the vernacular. When you went to Mass in 3rd-century Rome, you heard Latin for the same reason you hear English at an American parish today—because that’s the language people understand.

But as Latin faded and died out in everyday life, liturgical Latin stuck around. Not because it was mystical or magical, but because it was stable, precise, and widely shared across the Western Church. That stability became a real strength—Latin preserved theological clarity and kept the Church unified across different cultures and languages.

But—and this is crucial—Latin was never the substance of the rite itself. It was a vehicle, a tool, a common language. Important? Yes. Essential to what makes the Roman Rite “Roman”? No. I’m not anti-Latin, but it does not make the Roman Rite more Roman Rite-y, it just makes it more roamin’ Righty.

(I know how corny that is but I really couldn’t resist taking a swing at a little wisecrack there. Too inviting!)

Trent Did Not Create a New Mass

Let’s talk about the Council of Trent, because this gets misunderstood constantly. People treat Trent like it either saved the Mass from complete destruction or locked it in a time capsule for 400 years. Neither is true

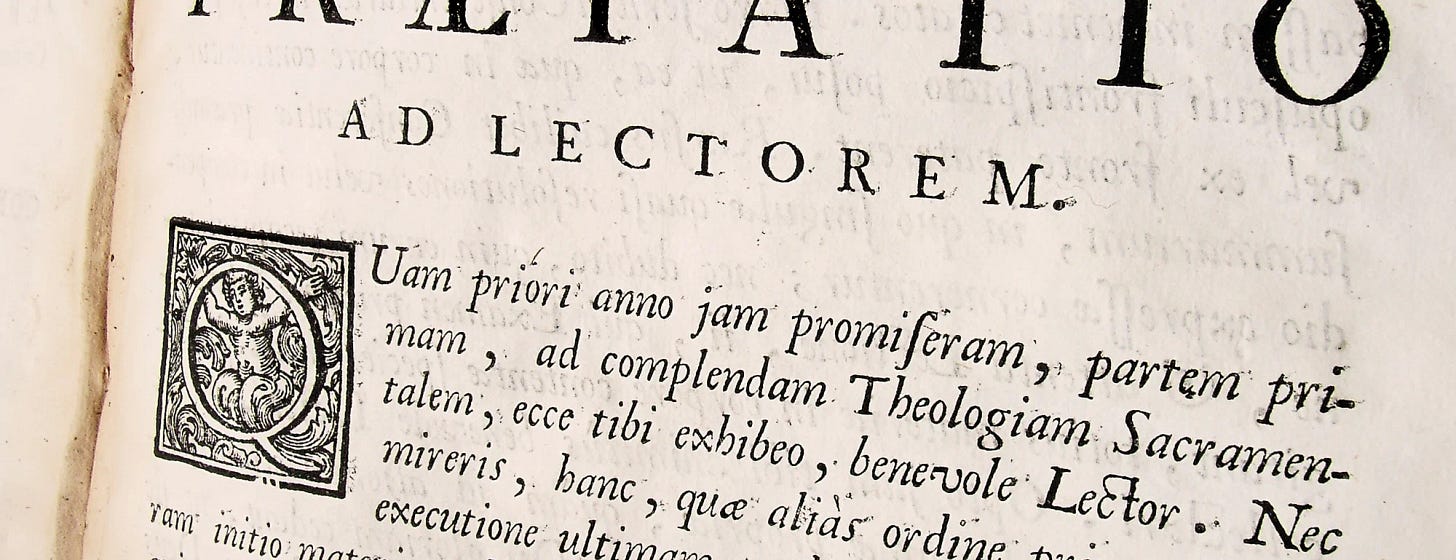

Here’s what actually happened. After the Protestant Reformation—when the Mass was being denied, gutted, rewritten, or just tossed out entirely—the Church had to act. Pope St. Pius V promulgated the Roman Missal in 1570, but he wasn’t inventing something new. He was standardizing what was already there.

What he codified was ancient: a Mass that had been in continuous use for centuries, cleaned up from late medieval clutter and local improvisations, and stabilized to prevent doctrinal erosion. The so-called Tridentine Mass wasn’t an act of nostalgia. It was an act of discipline and protection.

And here’s something people forget: Pius V allowed ancient rites with at least 200 years of continuous use to continue alongside his standardized Missal. Yes, he suppressed some problematic local variations of the Mass that had crept in—that was the whole point of standardization. But he didn’t claim there was only one legitimate form of the Roman Rite that could ever exist. Ancient rites like the Ambrosian, Dominican, and Carmelite liturgies were explicitly permitted to remain. The Church clearly recognized that there wasn’t just one legitimate way to celebrate the Roman Rite.

Think about that for a second. If Trent really believed there was only one valid form of the Mass, why let other ancient rites continue? The answer is simple: because legitimacy isn’t about aesthetic uniformity. It’s about substance, authority, and continuity.

“Organic Development” Isn’t a Free Pass

People love throwing around the phrase organic development and using it as license for a host of Liturgical novelties that could even make Martin Luther blush. Really when used correctly, it’s a helpful concept. When used poorly—as it often is— it becomes a rhetorical shield—a way to justify whatever you already believed about the liturgy, which happens to be the root of every mass abuse. So let’s be clear: Organic Development isn’t a blank check for Liturgical novelty or creative editing. Even if it were, the Church—not the individual, whether pastor, celebrant, or layperson—has sole and exclusive authority to write and sign it.

So let’s be clear about what organic development does not mean:

It doesn’t mean “no pruning” This happens with the Liturgy all the time, across the Church’s history.

It doesn’t mean “no reform”

It doesn’t mean “the Church can’t intervene”

It doesn’t mean “everything that develops naturally is good and should stay forever”

Organic development means continuity of substance alongside legitimate change of form. The Roman Rite developed organically because the Church governed it—adding prayers when needed, removing redundancies, revising calendars, simplifying rubrics, responding to real pastoral needs.

Left entirely alone, rites don’t stay pure and perfect. They sprawl. They accumulate. They get messy and confusing. A garden doesn’t stay beautiful without a gardener. Neither does a rite.

The Roman Rite Has Always Changed — Carefully

Between Trent and Vatican II, the Roman Rite kept evolving, though subtly. Calendars were revised. Rubrics were simplified. The entire Holy Week liturgy was significantly reworked in the 1950s—and nobody screamed “rupture from Tradition!!”

In fact none of this was treated as betrayal. It was stewardship. It was the Church doing what it’s always done: governing the liturgy with care (I’ll talk more about that in Part 3), making adjustments where needed, preserving what’s essential.

The real historical pattern isn’t “perfect unchanging stasis followed by sudden catastrophic rupture.” It’s measured, careful, authoritative reform carried out with theological awareness and prudence. That distinction is easy to forget when you’re caught up in liturgy wars—but it’s absolutely critical if we want to talk about this stuff honestly.

Descent Matters More Than Aesthetics

Here’s one of the most important things I want readers to understand if you’re going to think clearly about the Roman Rite: the legitimacy of a liturgical form isn’t measured by how old it looks but by whether it descends from the Church’s received tradition under legitimate authority1.

The Tridentine Mass (like the Novus Ordo) matters because it’s a genuine heir of the Roman Rite. Its prayers, gestures, structure—they all grow out of centuries of Roman worship. It has real roots, real substance, real continuity.

But that doesn’t mean the Tridentine Mass exhausts the Roman Rite. It doesn’t mean every liturgical form that came after it is automatically illegitimate or fabricated out of thin air.

Descent, authority, continuity of substance are the real criteria. Not our aesthetic preferences. Not what feels more “traditional” to you or me. Not whether you like Gregorian chant or folk guitars2.

If we’re going to argue about the liturgy then let’s at least argue about the right things.

Understanding the Roman Rite as a living, governed tradition prepares us for the harder question — the one most liturgical arguments are actually about:

Who has authority over the liturgy, and what are its limits?

That’s where this series goes next. If you’re subscribed, you’ll be notified when it’s published. If you’re not subscribed, you’re potentially flirting with eternal damnation, but you can fix that by subscribing below

Paid Members, don’t forget to check out “About the Art” below

Follow me X | Insta | TikTok | YouTube | Facebook | Discord

and my personal newsletter, CatholicFirebrand.com

FOOTNOTES

Why people get this wrong:

Because we tend to judge the liturgy emotionally rather than ecclesially. We confuse reverence with age, novelty with corruption, and authority with personal preference. Add in a few decades of bad catechesis and internet-driven absolutism, and people end up defending positions the Church herself has never held.

I’m a very traditional kind of Catholic. I don’t like folk guitars, I prefer pipe organ music. I like incense, I like Latin (used intelligently). I prioritize reverence, but I think some people have odd ways of understanding that word. My point is that the reader shouldn’t interpret this as an attack on traditional things, because it isn’t that. But we betray our our own claims of being “traditional/orthodox Catholics” when we impose our preferences on actual Sacred Tradition or use our preferences as measuring sticks against the legitimacy and authenticity of the Sacred Liturgy in any form.

About the Art:

The Council of Trent by Pasquale Cati is less a “painting” in the modern gallery sense and more a visual manifesto of Catholic authority.

(Paid Subscribers Only)